|

| Raghupati Dharua (left) and Satyaban Sahu (right) |

Illegal poaching is an ongoing issue all over the world. Whenever there is a poaching incident, the investigation involves authorities following clues and other crucial information which would lead them to the culprits. Once apprehended, the culprits are usually convicted and sentenced to considerable jailtime. But what happens when the culprits are released after serving time? Do they resort again to their illegal activities and the process is repeated all over again? Or do they find an alternative which steers them away from a life of crime? One such case was seen with two men named Raghupati Dharua and Satyaban Sahu from the state of Odisha in India. For thirty years, they were infamous poachers and labeled as "most-wanted" in both police and forest departments. But now, these men have renounced their life of crime by working as informants and assisting the forest department combat poaching and capture the perpetrators in Odisha's Debrigarh Wildlife Sanctuary. In their own words, the men wanted to give up poaching because their respective children are growing up and they did not want the younger generation to live in disgrace. Due to their familiarity with the dense forest and difficult terrain, the duo gave information on snares poachers lay out to catch or kill animals. One of the officials who is grateful for their help in protecting the sanctuary and its wild inhabitants is Anshu Pragyan Das, a divisional forest officer of the Hirakud wildlife division. In addition to being informants, Dharua and Sahu have other jobs in the sanctuary. For example, Sahu mans a gate at Zero Point of the sanctuary. Dharua, on the other hand, is a carpenter in the sanctuary's ecotourism facilities and also plumbing and electrical repairs.

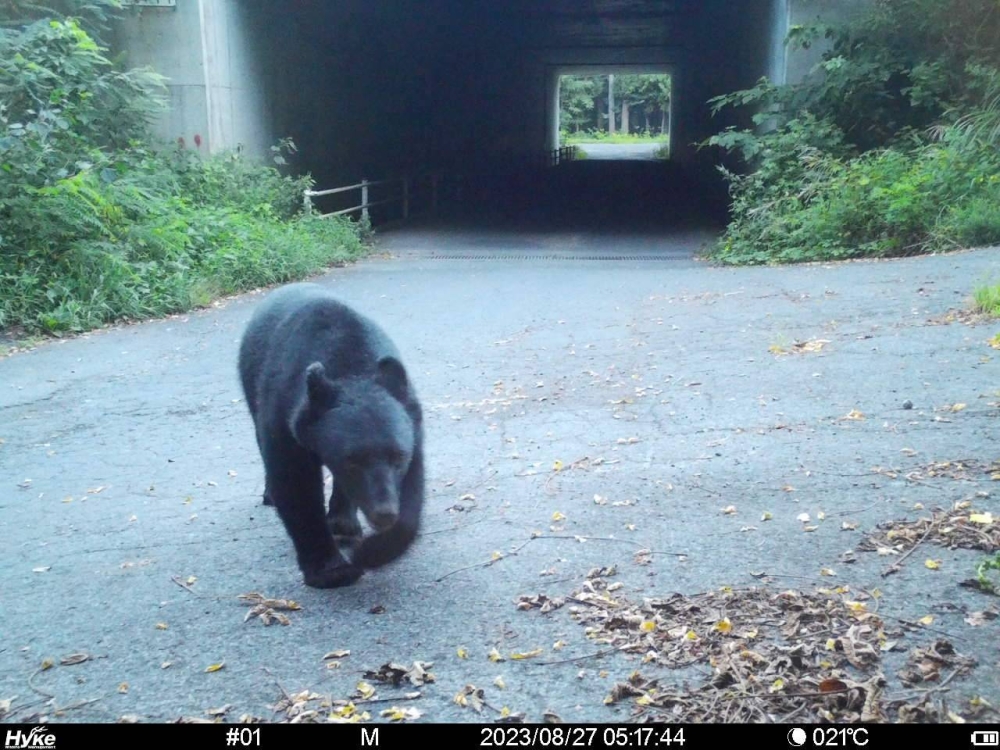

.jpg/1920px-Debrigarh_Wildlife_sanctuary_(38509512300).jpg) |

| Debrigarh Wildlife Sanctuary |

I cannot think of any better way to improvise the fight against poaching than recruiting former poachers in assisting wildlife officials in protecting the world's wild places and wildlife. This would be an alternative to the life of crime for them and provide a second chance. Furthermore, ex-poachers have an intimate knowledge of the inner workings in poaching gangs which would be beneficial for authorities in apprehending the gangs' active members and accumulate enough evidence to convict them of their crimes. It goes to show that it takes a thief to catch a thief. Raghupati Dharua and Satyaban Sahu are ideal examples of individuals who once used to make a living poaching wildlife, but decided to give up that lifestyle and turned over a leaf to assist in the battle against poaching. Each one of them had a rough past. Sahu, who hails from the village of Khajuria in the foothills of Debrigarh, dropped out of primary school and made a living grazing livestock before taking up poaching at 17 after his mother passed away. He was involved in a notorious tiger hunting case in 2018 for which he was sentenced to nine months imprisonment. He was arrested again in 2020 after being caught with a leopard skin. Since then, he turned his life around and is now working with the forest department earning Rs. 12,000 per month. He has even been involved in ecotourism activities. I really think that Sahu and Dharua should be seen as role models to various people living in the vicinities of protected areas in India and other tropical places. Their stories and experiences should be taken as life lessons by people who are either actively involved in any type of wildlife crime or even thinking of resorting to these types of illegal activities. I also believe that in countries where poaching is rife in protected areas, there should be special programs geared at people living in the margins of societies providing them jobs in working with wildlife and law enforcement officials in combating various wildlife crimes. It would very much help, especially when there are individuals who are knowledgeable in how poaching gangs and other wildlife crime syndicates function.